DLAB

In the summer of 2019, I found myself restless. I needed to do something to expand, to grow, I needed a challenge. More specifically I felt my technological capabilities were stalled. I was trying to learn visual scripting; dynamo and grasshopper and I had hit a wall. I didn’t use these applications in my day-to-day practice, but some of my students were using them and I didn’t feel like I could discourse with them about their designs on their level without a working knowledge of the tools being used. This idea relates to my general approach to technology, but I won’t digress here. It would be kind of like trying to teach someone carpentry or welding without knowing how to use any of the contemporary implements, CNC machines, digital MIG welders, plasma cutters, (these examples could be write-ups on their own) for example, when the students did know how to use them. At that point, we would be talking about the philosophy of carpentry, welding, and fabrication (not necessarily bad conversations, but limited), or our discussions would be about the nature of the objects created and not the process of creating them. Discussions of objects created are discussions of art. And while these discussions are vital and we had them as needed, I was not teaching art. Art and Architecture are not the same things. They overlap in meaningful ways but are disparate in equally meaningful ways. I was teaching students HOW to design buildings -- I was teaching architecture and I felt it was imperative I learn some contemporary, or forward-looking, methods.

So, I watched youtube videos and pillaged the online tutorials available through my university affiliation, but I couldn’t wrap my head around how to integrate these tools into a design process. I was reminded of a conversation I had with a student a few years before. The student told me their goal over the summer break was to learn Revit. I asked what their strategy was. Watch all the online tutorials available. Laudable, but insufficient I responded. You need a project.

It hit me, I need to follow my own advice; I needed a project. So I began searching. I found the summer DLAB program at the Architectural Association in London. From the website “DLAB experiments with the integration of advanced computational design, analysis, and large scale prototyping techniques.” I was hooked. The logistics of taking a one-month hiatus from your own small firm to go around the globe and learn some new skills that had no immediate apparent application to your day-to-day was a hard sell. In the end, we came to an agreement, and I booked the trip. I was going to spend four weeks, the latter half of July and the first half of August, in London.

I have a background in design, making, and computation. From carpentry and fabrication to working with CNC machines and machines in general and I was excited about that part of the course. The part of the DLAB opportunity that appealed to me most though was the advanced computation part--specifically, Grasshopper. And I was not disappointed.

Getting to London

Being as I have only flown across the pond a few times, and never on my own dime (that’s another story) I decided to try to make at least one extra stop. I flew over a few days early and stayed with one of my rugby mates -- Rui D’Orey Branco. Rui was a veterinarian in Portugal and came to Texas in 2015 to do his Ph.D. in animal science at Texas A&M, he joined my rugby club, and we became fast friends. In the summer of 2019, he was in Tunbridge Wells, south of London, working with a veterinarian. I spent a few days in this English village and Rui showed me around. Here’s a pic of us outside St. Nicholas Church Sevenoaks.

From Tunbridge, I took a train into central London. I don’t consider myself a total bumpkin, but my experience with public transit on the scale of the UK was rather limited. I did not do the typical thing of my generation and tour Europe upon completion of my undergraduate degree. I did do a month-long research project on the Normandy coast in 2004, but that utilized little public transit. I have navigated the Paris subway fairly easily, have gotten myself lost in the NYC subway system more than once, and move around on the Bay Area public transit very easily. Incidentally, the average French person was more helpful than the average New Yorker, but I attribute that to a language barrier. I speak a little French and I speak ZERO New Yorker, with the exception of expletives. Nevertheless, I ended up at my Airbnb, about a mile north of Bedford Square, with little incident. I am certain I looked the tourist part, walking (stumbling mostly) along with eyes cast upward looking at buildings.

A note on my lodgings -- I lived in an 8’x8’ room for three weeks. It was just like my first apartment in college, with the notable difference in cost and access to better coffee.

The Architectural Association is located in Bedford Square in London. The school is in a series of connected buildings that were originally housing. I don’t think I ever grasped the overall strategy for connecting all the spaces as it seemed at times circuitous, but that simply made moving around at any point during the day a bit of an adventure.

Program

The DLAB program was three weeks long and consisted of three main parts; Leaning, Design, and Fabrication. That's a little misleadning as learning spanned all three, so did design. The program spanned 21 days and we used all of them. The school was open from 10AM to 10PM and we would take an hour for lunch each day. This may seem grueling, but if you’ve gone to architecture school, you’ll understand, if not, I’ll try to explain.

There is a palpable energy when architects take on a design project. It starts a little slow, but it builds at a non-linear rate. There comes a tipping point when taking a break starts to be harder than the work--the challenge consumes. When this happens in a studio environment, by this I mean in a space shared with others who are tackling the same or similar problems, the energy feeds and the work is no longer work; it's just energy. You forget the rest of the world and become lost in the challenges. You forget to eat and when you do it tastes amazing. The first coffee of the day is a habit, the 3 pm espresso is earned and it tastes infinitely better. It is during these short breaks that magic can happen. The brain, or the mind perhaps, is a fascinating thing. We can work on a problem for hours and feel like we make no progress. Take a short break, focus the conscious on something more immediate, like lunch, coffee, or a drink, something that is primarily automatic where most of our action is routine or understood, and the mind will divert excess function to the unconscious. Then suddenly, while you’re having your coffee, a solution slaps you in the face -- a gift straight from the unconscious mind. This is why, I believe, good ideas happen in the shower. The body is moving, you’re accomplishing something that has to be done, and the mind takes that energy and connects ideas for you. But when you’re focused on something, intently, the mind gets myopic, it’s energy can’t branch out and connect to other things. That creative, that energy, cycle happened for almost the entire twenty-one days. It was the most addicting thing I’ve ever experienced.

A note on the weather

I have a friend from England. He told me the average London July/August would be quite nice. Highs in the 70’s. He was mostly accurate. With the exception of the first week. The UK experienced a heat wave. The temperature soared to over 100 degrees F. In Texas terms that’s high, but not unexpected for August. For the Londoners, it was, for intents and purposes, the end of the world. To their credit, not a lot of air conditioning there, so I get it. The afternoon of the heat wave the city was repairing a water line in the street in front of the school, so they temporarily shut off the water. The school does not have air conditioning. So, combine record-setting high temps with no water and the school decided to close for the afternoon. Seemed quite reasonable and responsible. So we moved to a pub, which also did not have air conditioning, but had beer. All was well.

Introduction

When you walk into the Architectural Association at Bedford Square it is a kind of surreal experience. I have visited many schools of architecture and they all have their own presence. Many of them have a certain grand notion. The Langford Architecture Center at Texas A&M is housed in a 1974 brutalist-style building. One of the last buildings of that style built in the US. The Univeristy of Colorado’s graduate program (during the year I attended) was located in floors 3-5 of a non-discript office building on, what was at the time, the western edge of downtown Denver. University of California Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design is in a brutualist-looking concrete structure. The Architecture program at Instabul Tech is a classical-styled building from the 18th century (I think, it might be older). The entire ETH campus is how I imagine the Swiss to be, clean, precise, and unpretentious. The architecture program at the University of Nebraska is in a building that looks like something out of Harry Potter. Where I am going with this? Well, the Architectural Association Bedford Square occupies a section of 18th century row housing. The general feel of the buildings is what I associate with Victorian-era London. I have little notion if this is accurate, with respect to dates of construction, but that’s how it felt. A rather unassuming block of masonry row housing with an understated, but elegant front door, with a humble metal sign that reads “Architectural Association”. Rather British I imagine. Of course, I could be way off on that comment, but I kinda doubt it. The point is, there was no grand entrance, no monumental presence. I suppose it doesn’t need it and I found the understated presence compelling and I identified with it. My grandfather was one of the last real cowboys in the Texas panhandle. He didn’t go in for the unnecessary, all the way down to the words he spoke, which were few. Clearly, if you’ve made it this far in the missive, I didn’t get that quality when it comes to the written word. He embodied the lyric "his pride won't let him do things to make you think he's right". All this is to say, when I walked through the understated door on the first day of DLAB, I felt at home and I was excited.

Creation - Lectures and Lessons

The first week of the program consisted of a series of lectures and training sessions. Both external and internal lecturers presented on topics including theories of design and connections to computation. We also had lectures on the geometry of curves and surfaces and algorithmic thinking. The lectures were intriguing the work presented was compelling. Between these lectures were intense grasshopper sessions. It was clear the range of knowledge in the group of twenty students was large, and we all had to get to a similar point. For me, this was challenging. We spent our days from 10 AM to 10 PM learning scripting. I would go back to my 8x8 room and deconstruct the script we built, trying to better understand what we were supposed to be learning. At some point, I decided to trust myself and let go of the compulsion to redo everything we did that day. I just let myself take in what was happening.

A note on the group

There were twenty of us from all over the world. We spanned in age from early twenties to early forties. I think I was one of the oldest in the group at 42. English was the primary language, but I enjoyed learning what other languages people spoke; Spanish, Dutch, Arabic, Chinese, and Hindi. I am certain I am forgetting some, or perhaps not representing some accurately and I apologize. It was a wonderful cultural overload.

Welcome to the basement

The basement of the AA is a magical place. It has a full 4x8 CNC machine, a 3D printer lab, and an array of laser cutters. As if all that wasn’t enough there are also two Kuka Robotic arms. As part of the first week, we were trained on all these machines. To date, I had not done much 3D printing, but I am familiar with the idea of extruding material into layers. I printed some things on a dust matrix printer in the nautical archaeology lab in 2003. I’ve also been working with the idea of cutting on 2D plane with a router since 1999. A laser cutter is not much different and I’ve used them to make a few things. The robotic arms were a whole new ball game for me. It took me a while to wrap my head around the possibilities. Turns out, I shouldn’t have wasted the effort, it’s what we would be doing for the rest of the workshop.

Design charrette

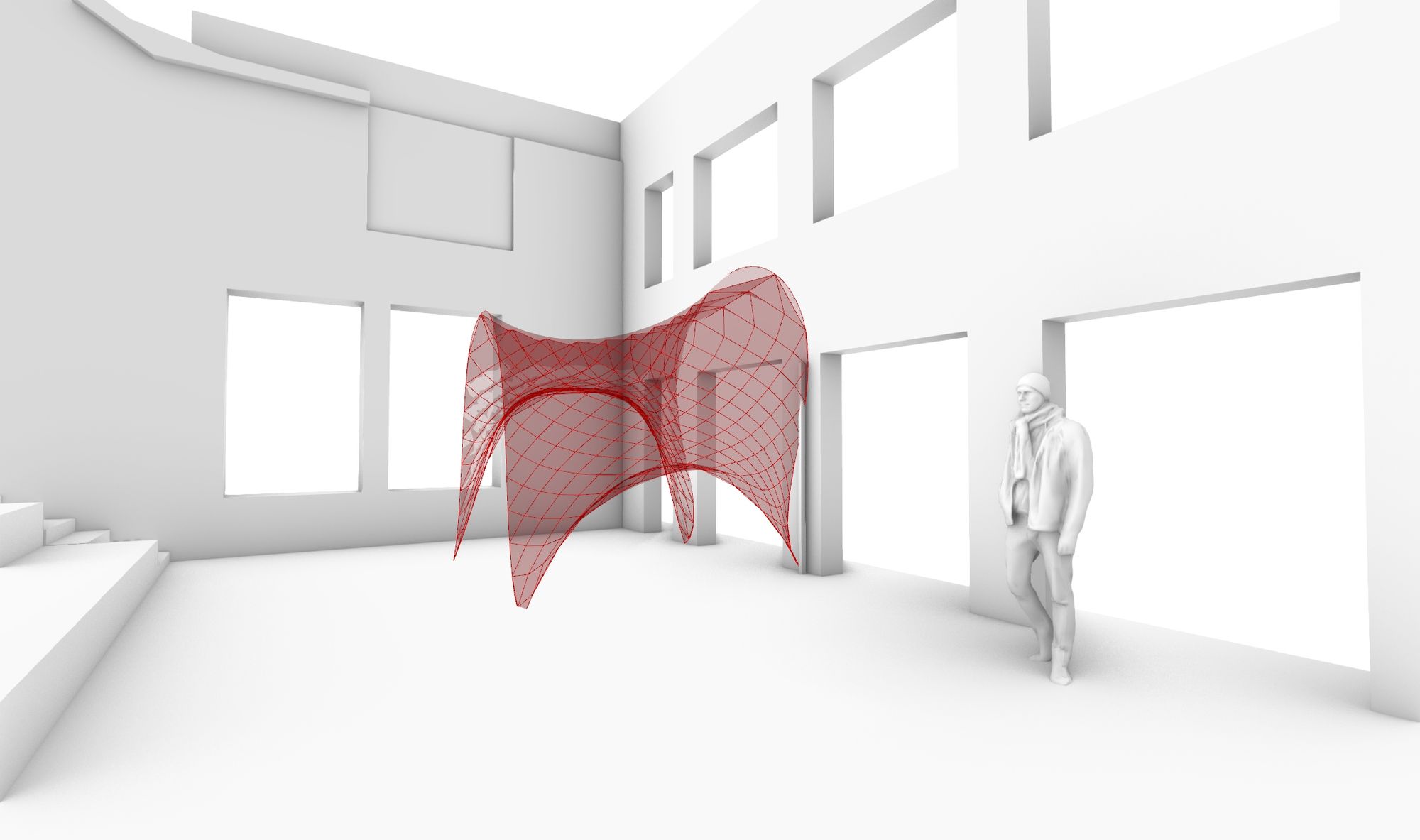

Toward the end of the first week we broke into groups of 5 and were given a design project. We were tasked with designing and self-supporting canopy structure to cover a workbench in the interior courtyard, but first we had to learn how to interface with Kuka arms. Our first task was to make the arm paint. Nothing major, just our team name. Turns out Kuka has a grasshopper plug-in so the task was not as challenging as it might seem. From here we learned that the goal of the workshop was to explore forms that could be created with spiffing. Spiffing is a process of creating a cone within a sheet of metal. In this application spiffing uses a spindle, essentially a motor, with a smooth steel bit, attached to the end of the Kuka arm. While the bit spins the kuka arm rotates in concentric widening circles while moving down in the Zed axis. The result, with a little lubricating oil added, is a cone shape molded into a piece of zinc sheeting. This would be the concept we would explore in the creation of our canopy structure. Using our newfound algorithmic skills combined with the understanding of the Kuka arm and spiffing we set about designing a self-supporting canopy structure.

A comment on the process

In retrospect the way we were introduced to these concepts was transformational. Rather than being told about the theory, shown some images, and told to design, how I have normally been exposed to design exercises, we were taken along a different route. We were shown theories of algorithmic design and given instruction on the basic skills of implementation. This was bolstered by in depth explanations of computational geometry. We were then required to use that knowledge to make a machine do simple tasks, like paint, and then more complex tasks like spiffing a small panel. Then we were asked to imagine bigger, change the scale as it were, and design. This approach was similar to how I learned carpentry. A basic understanding of the properties of wood. I learned about the different species commonly used, their grain characteristics, their relationship to structural capacity, and their aesthetics. I had to take tree trunks and mill them into usable pieces. Incidentally, I did a lot of this before I was allowed to actually make anything. Then I learned the basics of joinery combined with the idea of the cutting circle. Then I was given small tasks to learn or experiment with, or in my case mess up, some small joints. After I had messed up a few I was told the secret. A good carpenter is not one who gets it right the first time, but one who knows how to recover from a mistake and keep going. Reminded me of learning to draw. Lots of practice. A major difference between carpentry and drawing is at no point in all my years of drawing were my fingers ever at risk of being removed from my hand. So, the process of learning carpentry involved learning how to cut and assemble wood in such a way that the end product was beautiful and all digits remained intact. Experience being that thing you get moments after you need it, I did put a dent in the band-aid budget my first year in a mill shop. And don’t get me started on splinters. The point was, we spent some time learning basic skills, computational and mechanical, before we were asked to design with anything. Incidentally, I learned the Kuka arms could move loads much heavier than myself and if I got in the way of an arm while it was moving, well it didn’t really care, it would just move me. Which is another way of saying we got a good, hands on, education of Newton's first law, and Kuka arms are heavy.

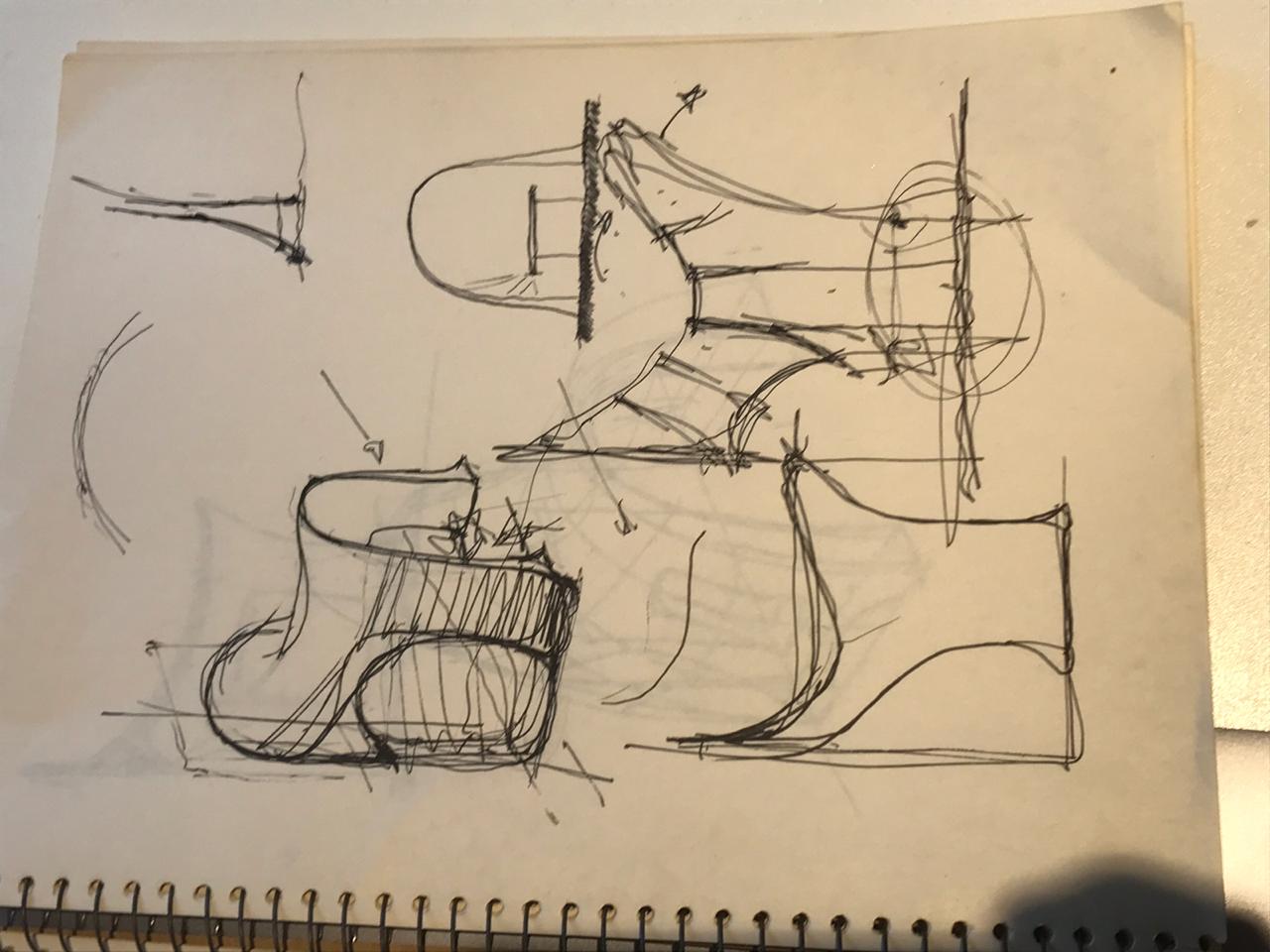

A brief interlude on sketching

I’ve always had a knack for drawing. Over the years I have met people who are much, much better than I, but i guess I just refuse to give up sometimes. So I just keep drawing. A lot. Turns out, the others in my group were more than happy to let me draw ideas while they described things, expound upon their initial sketches, and comment on mine while I did them. It was a fantastic collaboration. Several times I ditched what I was working on and started over. In the end we had a pretty good concept and set about to model it. Here’s where I took a backseat as, while I could sketch, others could grasshopper. I think they got a little annoyed as I asked for explanations of what they were doing constantly. I was also spending my evenings reviewing files they created, working to understand grasshopper scripting. In the end our concept was pretty simple. It was based on an arch, the original self-supporting structure. We included some spiffing, which at this point was primarily aesthetic. Although we had a notion that this could be structural and it goes like this. When we spiff two panels, essentially make two cones, and put the small ends of the cones together it creates two panels spaced apart by the double the spiff depth. This is essentially increasing the Ix value of the cross section. We built several models of to illustrate the idea and test the behavior. The instructors took all four concepts and Ideated a final design.

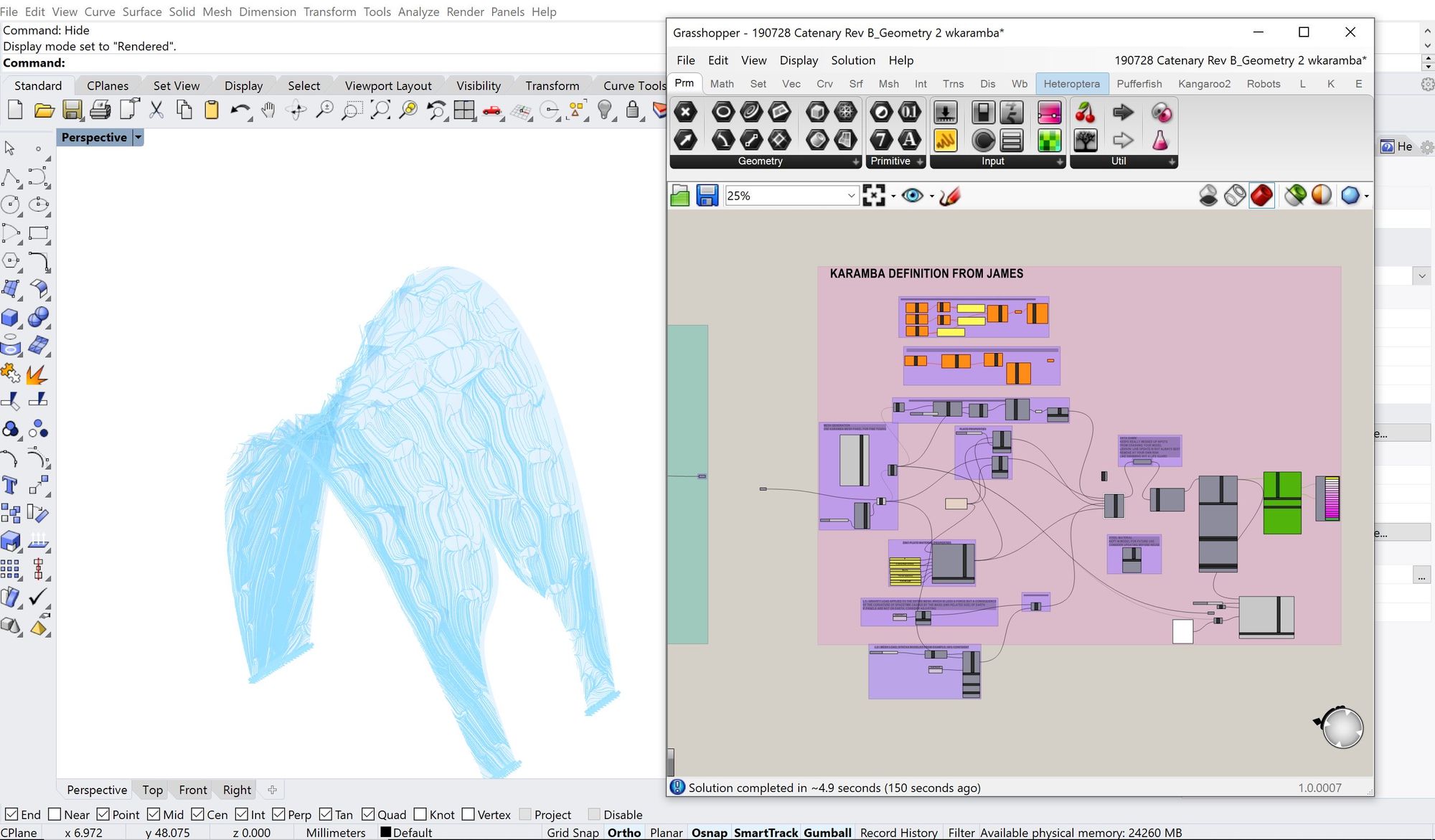

Engineering team

At this point the group of twenty broke into groups for design, engineering, and fabrication. I chose to be on the engineering team. I very much wanted to learn Karamba. I had some background with FEA, using Abaqus in 2001 to analyze a ship hull. Seems FEA has progressed quite a bit since then. Our goal was pretty simple -- to get the xy forces to resolve at the base without the need for a tension rod. Separating the two “skins” with the spiffing helped tremendously. In the end we constructed a large foot on both ends, which was heavy enough to resolve both friction and the remaining x forces. While we were doing this another group setup fabrication procedures, experimented with hold-down methods, and prepared for the fabrication process. Another group panelized the canopy structure in Grasshopper. This resulted in all individual panels being “flattened” into profiles that could be milled on the CNC machine and then loaded into the hold-downs and spiffed.

Fabrication

We worked twelve hours per day for at least four days. Cutting panels on the CNC mil. Spiffing the panels and laying out the panels in proper order. The last day of the class the whole assembly came together. The original canopy would have had three feet as the canopy “split” on one side and formed two legs. This was intentional to add geometric stability. It was determined fairly early during fabrication we were not going to have time to cut and spiff all the necessary panels. So, we only built, essentially, half the canopy. We made two large feet out of laminated MDF. The initial panels were bolted into these feet and construction began. Two sides of an arch building up to meet each other. I’d like to say the whole thing came together simple as cake, but that didn’t happen. Zinc panels with milled edges are sharp and fabrication tolerances add up. The whole thing came together and it was beautiful, but it required a little “adjustment” along the way from some muscle and maybe a hammer. I was reminded of my favorite construction document note “HTF&PTM” -- Hammer To Fit & Paint to Match.

In the end, we had an assembled canopy of spiffed zinc panels. It was beautiful. Any time I get to take an idea from my head and make it in the real world it is a rewarding experience. In this instance, it was an idea generated across twenty-five heads and realized with more than fifty hands. There were tense moments and we had to work together to overcome challenges. But in those moments we came together as a team. The entire experience was amazing. I would recommend it to anyone. I expanded my grasshopper skills and learned how to use a Kuka robotic arm. More than that, I made some friends, and learned some construction terminology in other languages! In the end, I went back to Texas energized and equipped with an entirely new skill set.