A First Birthday Present

My daughter was born in 2003. During her first few months of life, I was in my last few months of graduate school working on my thesis design. New parents and architecture students sleep about the same amount. I thought about the rocking horse my grandfather made for me. He taught me woodworking and carpentry and I knew I could recreate his design, but I also thought I could do better, or at least something different.

When I was sixteen I worked for a millwork carpenter. I started out by drafting shop drawings by hand. Because I knew AutoCAD I brought his little millshop in the twentieth century. Shortly after this, he invested in a CNC machine, and because I “knew computers” I got the joyous task of helping him make it operational. A few years later, in 1999 he would get a much larger machine with a vacuum and bed and automatic tool change. I helped him take this operational as well. By this point, there was specific software for visualizing cabinet designs in 3D producing fully nested panels alongside cut sheets, and then sending all the GCode to the machine on the shop floor. Essentially the skills we learned on the first machine were all coded into software and the role of the carpenter became one of loading sheet goods, operating a terminal, and unloading cut-out parts.

Essentially within the 6-8 years that I was a carpenter, I learned cabinet design by drafting shop drawings, first by hand, then in CAD. Then assemble lists of panels and parts and turn those drawings and lists into built cabinets with methods that had not changed in close to a century. The tools to support the methods had improved drastically. Table saws were much better, safer, and easier to use, there were specific machines for milling and joining raised panel doors, and methods for cutting and assembling face frames made the process much smoother. There were also entire machines for doweling cabinet pieces for joints. Don’t get me started on nail guns the cordless drill. I learned to use those tools to make beautiful cabinets. Cabinet design was joinery at its finest. Then we got a CNC machine. Within a short four years, all of the skills I worked so hard to learn were rendered obsolete. The software would visualize the entire kitchen design and generate cut sheets, counts of hinge, door, and drawer hardware, and with literally a push of a button, cut out all the panels, including the raised panel doors. The software would even put a small dimple where I was to put a screw if it was needed. In a few short years, I watched the skills of carpenters shift to advanced IKEA assembly.

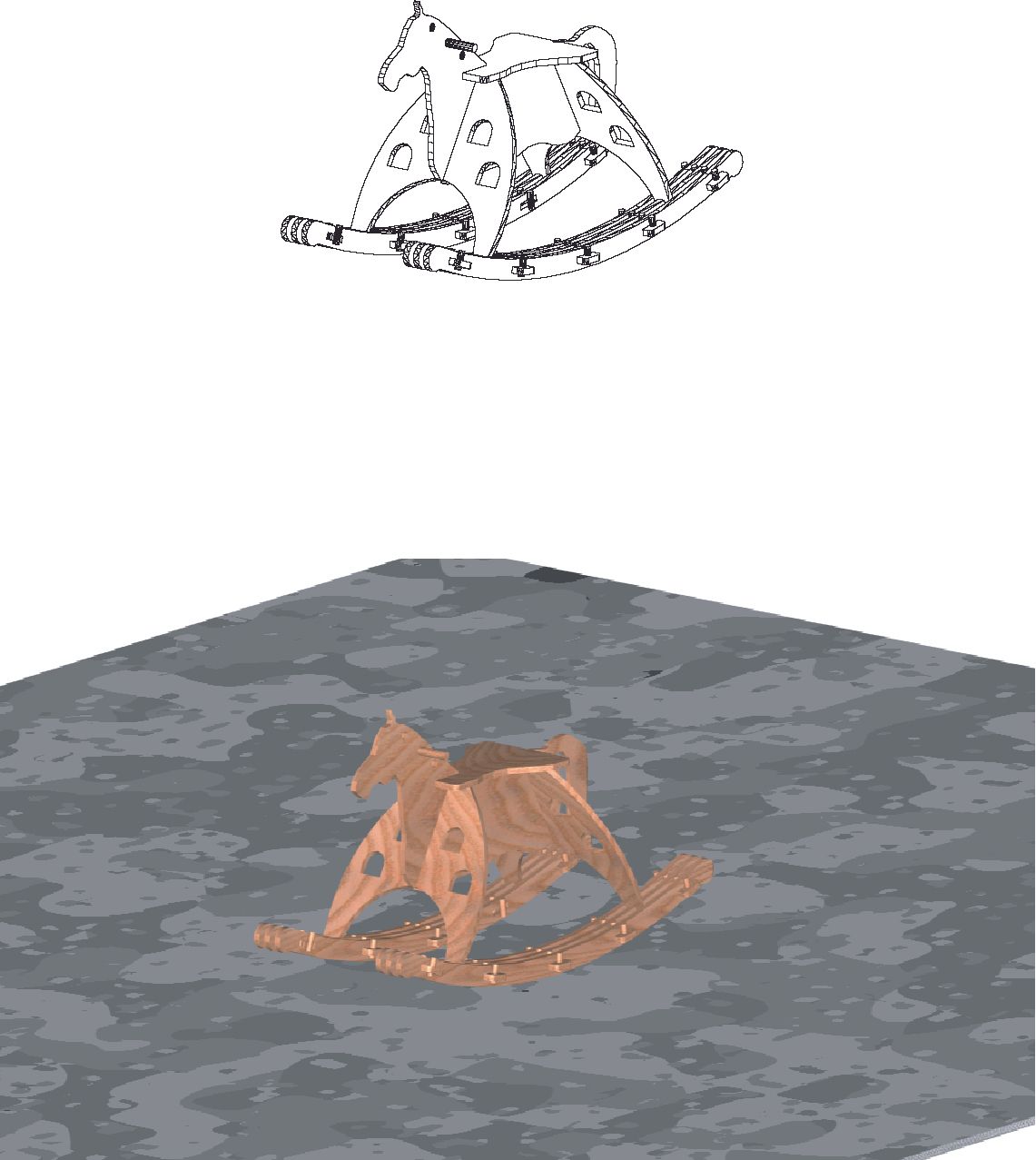

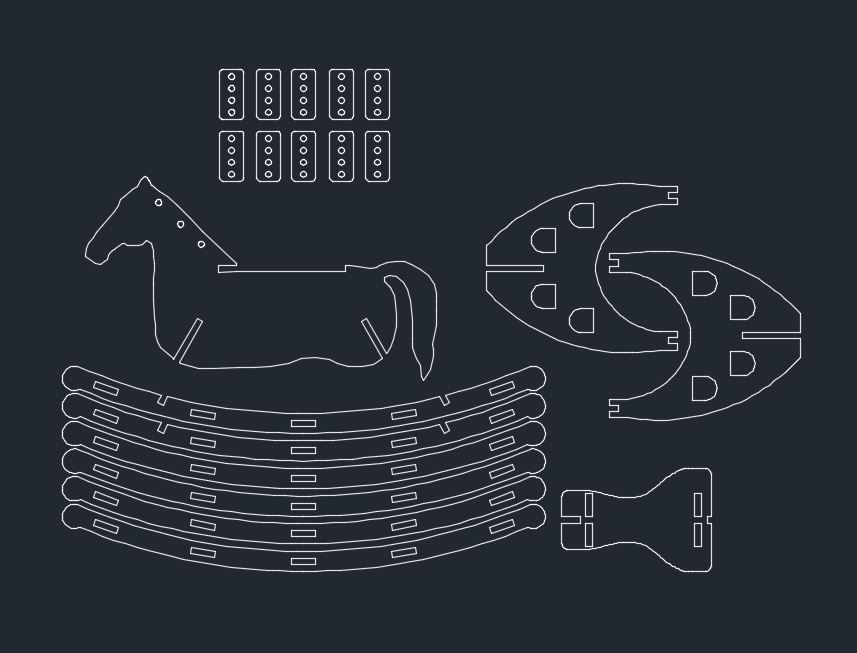

Let’s get back to the rocking horse. I had moved on from the mill shop and was learning to become a designer and an architect. I wanted to make my daughter a rocking horse and I wanted to flex the skills I had learned. So I designed one around the principles of 2D milling and used furniture-grade baltic birch. One of the key elements of the design was to assemble the entire piece without mechanical fasteners – no glue, screws, or nails; all fitted joints (I would later use this idea in a structures class for students to model trusses). The body of the horse breaks down flat for packing. The rails were a challenge. The whole design needed ballast to keep the weight low. To accomplish that I made the rails an assembly of three cut pieces assembled in a mortise and tenon style.

A year before I had worked on the Uluburun modeling project. I created an FEA model of peculiar mortise and tenon style from 1300 B.C. I guess that influenced the design of bottom rail joints.

The rocking horses were quite nice. My daughter loved it. I even made a few more on commission.

All this happened in 2003-2004. I did all this with AutoCAD and used the CND software to generate the GCode. I had not yet explored Rhino, but that would change.